When 6-year-old Harper Clyde looked through the microscope, she immediately burst into tears. She knew she was looking at a tiny replica of the injury that caused her brother Tyler to nearly die as a newborn and continued to cause him suffering. On the microscope slide was a cross section of a mouse diaphragm — a muscle that helps all mammals to breathe — and it had a big hole in it.

Can we make the diaphragm grow better? Can we somehow help the herniation? That’s the long-term goal of a group of researchers at University of Utah Health, KSL News reported.

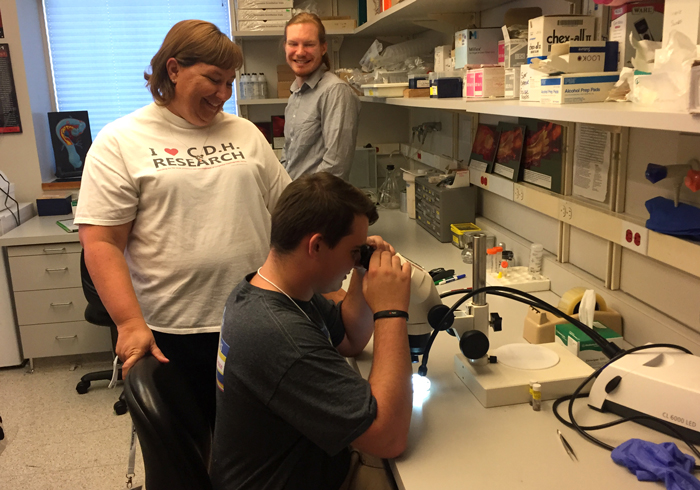

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), a not-so-rare birth defect that occurs in about 1 in every 1,600 births. The Clyde family and other families affected by CDH were visiting laboratories to learn about the biology of CDH and the research.

CDH weakens the diaphragm, causing a rupture that kills half of children born with the condition. Even when the hole is repaired through surgery, there is the danger that it can tear again, anytime. That’s what happened to Tyler when he was 14 years old. To save his life, he underwent his third major surgery to repair his diaphragm. Today, at age 16, he and his parents live in fear that it could happen again.

Because the biology of mice and humans are so similar, Scientists are able to carry out research with these animals to determine what goes wrong in human babies with CDH. The diaphragm is greatly weakened when muscles don’t form properly due to genetic defects. With this knowledge in hand, they are now testing innovative methods to fix the flaw at its source by adding repaired genes back to the fetus while the diaphragm is still developing.

While in the investigation and initial testing phase, this type of work can only be carried out in animals. The research could result in a completely novel way of preventing the birth defect by helping the diaphragm to form properly while the baby is in utero.

“Research like this gives us so much hope,” says Hope Clyde, Tyler and Harper’s mother. “Our goal is to help scientists find out why this happens.”

Learn more:

U Scientists Seek Answers to “Loneliest” Diagnosis

New Insights into the Little-Known but Common Birth Defect: Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia